english version follows.

En 2008, la crise précipitait le monde dans la chute de sa courbe. De nombreux états virent leur équilibre social et financier chavirer. L’éclatement des bulles spéculatives bouleversait les paysages du monde, la faillite des marchés immobiliers se répercutant dans les foyers comme un circuit de dominos.

Les crises économiques et politiques s’accompagnent souvent de phénomènes culturels alternatifs, qui recherchent une forme de compensation et de contrôle à travers les apparences. Si le bling-bling de la pop culture des années 2010 était le contrepoids de la rupture soudaine d’une atmosphère stable et prospère, comment le contraste entre un univers visuel particulièrement tourné vers les objets chers et la paupérisation progressive des classes moyennes inspire-t-il alors aujourd’hui le vocabulaire artistique?

Dans son essai Dreamwork / MEMORY DISORDER / à mon seul désir, présenté à l’occasion de l’exposition Protect Me from What I Want, la curatrice Anouska Kobus convoquait les dynamiques de l’affect qui accompagnent les désirs issus du capitalisme libéral et la poursuite de modèles d’accomplissement illusoires à travers l’accumulation de signes extérieurs d’appartenance ou/et de richesse. L’exposition réunissait ainsi différentes interprétations plastiques de cette confusion émotive que provoque la quête de la satisfaction selon un éventail de performances standardisées. Une invitation en somme, à envisager nos désirs via l’identification des systèmes qui les conditionnent.

Protect Me from What I Want curated by Anouska Kobus. Possibly Sometime Tomorrow (Paris). Avril 2025. Photo: Alia Nura.

Dans cette quête d’identité sociale, de statut, d’accomplissement–ici à travers l’accumulation de propriétés–, il y a quelque chose de désespéré ou d’obsessionnel mais de très sincère. Comme Sisyphe et son rocher, nous entretenons un circuit de récompense qui relierait consommation et sensation de parachèvement. Les accessoires de ce système d’avoir pour être, sont autant d’empreintes terrestres qui illustrent ces mécanismes jusque dans leur négatif.

Par exemple, dans la série La Casa de Oro y Celulares (2022) de Carlos Reyes, des plateaux-présentoirs vides exposent des démarcations sur le velours dues à une exposition prolongée au soleil. Les zones épargnées par les brûlures dessinent les contours des objets de valeurs qui les ont préservées : bijoux, croix ou médailles. La lumière et le temps inscrivent alors sur le tissu l’attente de l’acquisition, la présence de l’objet et sa disparition, la possible liquidation d’un stock. L’étoffe synthétique est marquée comme une preuve de l’existence passée et de l’échec probable d’un marché.

Les présentoirs, écrins ou boîtes deviennent autant d’architectures qui présentent ou préservent les choses qui y sont entreposées. Comme de petits cercueils, ces formes solides matérialisent bien davantage que leur contenu. Petites morgues, elles s’accumulent et dessinent des paysages de contenants, des montagnes d’emballages de plus ou moins bonne facture: la qualité de ces derniers censée présupposer celle de son produit protégé. Comme les maisons des gens.

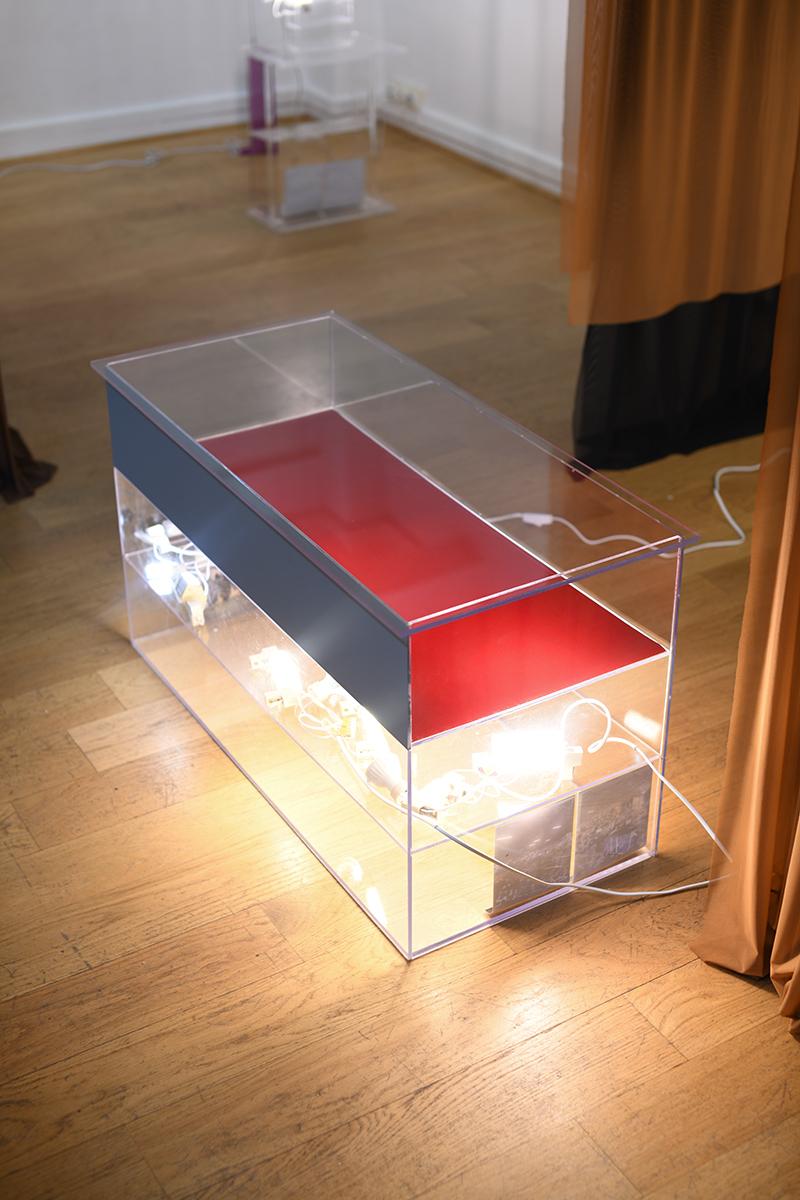

Cecil Hotel, 100x50x50cm, mirror panel, red velvet, light bulbs, fixtures, wagos, electric cords, acrylic sheets, glue, photographs, 2025.

Hélène Yamba Guimbi. Dazzle, Tether. Vue d’exposition. Tonus (Paris). Avril 2025. Photo: courtesy de l’artiste.

Quoique, avec la tokenisation des symboles populaires, peut-être verra-t-on bientôt apparaître des bagues Cartier dans des cires babybels. Cette balance entre toc et chic miroitait au printemps 2025, à travers les plexiglas d’Hélène Yamba Guimbi, ‘Hot Spot’ et ‘Cecil Hotel’ –présentés à l’occasion de son exposition ’Dazzle, Tether’ à Tonus.

Des tissus souples et des perles brillantes arrangeaient une skyline transparente d’acrylique et de colle. Tout est plastique, et le pétrole se sublime en de séduisants solides. Le texte de Salomé Burstein qui accompagnait l’installation décrivait la symbolique et le pouvoir que dégagent les auxiliaires de la fabrication de nos désirs. Autant de panneaux, de slogans et de merchandising qui manipulent et cultivent nos instincts de possession et d’accumulation en recouvrant les parois de nos décors.

Hot Spot, 90x50x50cm, saltwater pearls, velvet, light bulbs, ring light, fixtures, latex, wagos, electric cords, acrylic sheets, glue, thread, photographs, 2025.

Hélène Yamba Guimbi. Dazzle, Tether. Vue d’exposition. Tonus (Paris). Avril 2025. Photo: courtesy de l’artiste.

Finalement le chaland serait autant prisonnier de la vitrine que l’objet de l’autre côté. Les coussins de faux velours: des pièges comme des baudroies qui agitent un leurre scintillant pour attirer vers elles et se repaître des proies qui y succombent. Il se pourrait que cette phototaxie positive s’illustre par un vernissage. Ainsi, le soir de celui d’Hanna Rochereau au sein de l’hôtel particulier parisien de la galerie Hauser&Wirth, un ballet de cheveux plus ou moins argentés s’est pressé dans les escaliers étroits d’un immeuble du 8ème arrondissement, pour se réunir autour d’un énorme meuble de bois lustré, fait de petits cabinets vitrés, de tissus soyeux et de bolducs rebondis, sans rien dedans. Une énorme caisse vide qui repoussait les curieux vers les murs, sur lesquels étaient accrochées les portraits de grands paquets muets.

Installation view, ‘Hauser & Wirth Invite(s),’ Hauser & Wirth Paris, 2025. © Hanna Rochereau.

Courtesy the artist, Shmorévaz and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur.

Coincés entre ces emballages variés, les invités discutent de tout ce que cela veut dire, parce qu’il est indispensable de trouver un sens qui puisse combler le silence. En ne présentant rien, les présentoirs semblent renvoyer à l’absurdité ou au cynisme du monde auquel participe l’espace qu’occupent celles et ceux qui les regardent. La boîte à bijoux vide, ce sont peut être les quatre étages allumés rue François 1er, qui perdrait leur sens si, comme déconsacrés, étaient dépourvus des œuvres qui les ornent.

Installation view, ‘Hauser & Wirth Invite(s),’ Hauser & Wirth Paris, 2025. © Hanna Rochereau.

Courtesy the artist, Shmorévaz and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Nicolas Brasseur.

Plus fidèles au model réel quoique plus absurdes encore, les coffrets de Nora Guislain présentés à Concert en juin 2025 en duo avec Léopold Gaillard, défient la gravité et les visiteurs. Gargantuesques, ces objets agrandis du quotidien revêtent une dimension anthropomorphique. La chose change d’échelle et nous apparaît sous un jour nouveau, il s’agit alors d’un objet différent.

Seekers. Nora Guislain, 2025.

Second Fiddle, Nora Guislain & Léopold Gaillard. Concert (Villejuif). Juin 2025. Photo: Nora Guislain.

Après le poisson des abysses, la boîte à bijoux donne l’impression d’une bouche vorace de Sans-Visage (顔ナシ, Kaonashi), capturant et entreposant compulsivement dans son antre de satin, les corps qui se présentent face à lui; comme un curieux cercueil. Cette absorption hypothétique porterait alors l’objet ou le corps vers un état statique, à la fois protégé de l’extérieur mais menacé de disparaître, comme Jonas (ou Pinocchio).

Se préserver des choses publiques dans le confort de l’absence ou du mutisme menace potentiellement l’individu d’une séparation du monde, puisque, se soustrayant à la vie publique, commune et populaire, il peut en être progressivement mis au ban. La boîte à bijoux est bien un petit coffre fort, où les choses publiques (bijoux destinés à l’apparat et la démonstration via leur exposition) sont rangées, entreposées, à l’ombre du monde dans des entrailles transitoires entre intimité et exhibition.

Seekers. Nora Guislain, 2025.

Second Fiddle, Nora Guislain & Léopold Gaillard. Concert (Villejuif). Juin 2025. Photo: Nora Guislain.

Se rejoue aussi la performance de la représentation de soi dans l’espace public, à travers ces objets tendus, béants. Ils deviennent des espaces désespérés par leur incomplétude intérieure, et se déploient à l’extrême. Nora Guislain compose par ailleurs avec un choix de matières qui convoquent des vocabulaires assignés et des codes de séduction précis. Ces boîtes bredouilles, sont semblable aux individus qui se contraignent pour convenir aux normes, soumis à la supputation que la seule forme de réussite se manifeste dans l’accomplit.

Sans titre. Photo: Adèle Anstett.

La relation à l’objet qui se dessine à travers cette série d’exemples ne relève ni de l’angoisse ni de la nostalgie qui suivrait symptomatiquement la disparition de ce dernier. Il s’agirait plutôt d’un renoncement.

On ne cherche pas à compenser l’absence ou la perte de ce que l’écrin a contenu, il est intéressant parce qu’il a contenu quelque chose auparavant mais que ce n’est plus le cas. Il a été dépourvu de la fonction pour laquelle il a été conçu et qu’il a su remplir, et pourtant, il en reste imprégnée.

Cette désaffectation ne rend pas la boîte à bijoux inférieure, ni supérieure. Il ne s’agit ni d’une aliénation ni d’une muséification, elle ne gagne ni ne perd, seulement change de statut : la boîte devient parfaitement inutile. Au lieu de chercher à redéfinir les choses en dehors de leur destination d’origine, il s’agit d’abandonner ponctuellement la quête de signification dans un univers trop verticalisé. L’appréciation de ce type d’objets pourrait être alors une forme de réaction spécifique à l’inutilité, aux choses qui échappent au circuit de productivité et qui sont mises de côté sans être jetées (échappant à leurs responsabilités ?). Qui restent là, pour rien. Des coffrets complètement ouverts mais sans aucune expectation. Peut-être libres ? ou morts.

EN

In 2008, the crisis precipitated the world into decline. Many countries saw their social and financial stability collapse. The bursting of speculative bubbles shook the world, with the collapse of property markets sending shockwaves through households like a chain reaction of dominoes.

Economic and political crises are often accompanied by alternative cultural phenomena, which seek a form of compensation and control through appearances. If the bling-bling of 2010s pop culture was the counterweight to the sudden rupture of a stable and prosperous atmosphere, how does the contrast between a visual universe particularly focused on expensive objects and the gradual impoverishment of the middle classes inspire artistic vocabulary today?

In her essay Dreamwork / MEMORY DISORDER / à mon seul désir, presented in the show Protect Me from What I Want, curator Anouska Kobus explored the dynamics of emotion that accompany the desires born of liberal capitalism and the pursuit of illusory models of accomplishment through the accumulation of display of belonging and/or wealth. The exhibition thus brought together different artistic interpretations of the emotional confusion caused by the quest for satisfaction according to a range of standardised performances. In short, it is an invitation to consider our desires by identifying the systems that condition them.

In this quest for social identity, status and fulfillment – here through the accumulation of property – there is something desperate or obsessive, but also very sincere. Like Sisyphus and his rock, we maintain a reward cycle that links consumption and a sense of achievement. The accessories of this system of having in order to be are like earthly imprints that illustrate these mechanisms, even in their negative aspects.

For example, in Carlos Reyes’ series La Casa de Oro y Celulares (2022), empty trays show marks on the velvet caused by prolonged exposure to the sun. The areas spared from burning outline the contours of the valuable objects that preserved them: jewellery, crosses or medals. Light and time thus inscribe on the fabric the anticipation of acquisition, the presence of the object and its disappearance, the possible liquidation of stock. The synthetic fabric is marked as evidence of past existence and the probable failure of a market.

Display cases and jewellery boxes become architectural structures that present or preserve the items stored inside them. Like small coffins, these solid forms embody much more than their contents. Like small morgues, they accumulate and form landscapes of containers, mountains of packaging of varying quality, the quality of which is supposed to reflect that of the product it protects. Like people’s homes.

Although, with the tokenisation of popular symbols, we may soon see Cartier rings appearing in Babybel waxes. This balance between tacky and chic shimmered in the spring of 2025, through Hélène Yamba Guimbi‘s Plexiglas, “Hot Spot” and “Cecil Hotel” – presented at her exhibition “Dazzle, Tether” at Tonus.

Soft fabrics and shiny beads arranged a transparent skyline of acrylic and glue. Everything is plastic, and oil is sublimated into seductive solids. Salomé Burstein’s text accompanying the installation described the symbolism and power emanating from the auxiliaries of the manufacture of our desires. So many signs, slogans and merchandising items manipulate and cultivate our instincts of possession and accumulation by covering the walls of our decor.

Ultimately, the customer would be as much a prisoner of the shop window as the object on the other side. The faux velvet cushions: traps like anglerfish waving a glittering lure to attract and feast on the prey that succumbs to them. This positive phototaxis could be illustrated by a vernissage. On the evening of Hanna Rochereau‘s vernissage at the Hauser&Wirth gallery’s Parisian mansion, a ballet of more or less silver hair crowded into the narrow staircase of a building in the 8th arrondissement to gather around an enormous piece of polished wood furniture, made of small glass cabinets, silky fabrics and plump ribbons, with nothing inside. A huge empty box that pushed the curious towards the walls, on which hung portraits of large silent packages.

Stuck between these various boxes, the guests discuss what it all means, because it is essential to find a meaning that can fill the silence. By presenting nothing, the displays seem to refer to the absurdity or cynicism of the world in which those who look at them participate. The empty casket could be the four lit-up floors on Rue François 1er, which would lose their meaning if, like deconsecrated buildings, they were stripped of the works that adorn them.

More faithful to the real model, albeit even more absurd, Nora Guislain’s Seekers, presented for Second Fiddle at Concert in June 2025, in a duo with Léopold Gaillard, defy gravity and visitors. These gargantuan, enlarged everyday objects take on an anthropomorphic dimension. The thing changes scale and appears to us in a new light, becoming a different object.

After the fish from the abyss, the coffret gives the impression of the voracious mouth of No-Face (顔ナシ, Kaonashi), compulsively capturing and storing in its satin lair the bodies that come before it, like a curious coffin. This hypothetical absorption would then bring the object or body to a static state, both protected from the outside world but threatened with disappearance, like Jonah (or Pinocchio).

Preserving oneself from public matters in the comfort of absence or silence potentially threatens the individual with separation from the world, since, by withdrawing from public, communal and popular life, he or she may gradually be ostracised. The jewellery box is indeed a small safe, where public subjects (jewellery intended for display and demonstration through exhibition) are stored, kept in the shadows of the world in a transitional space between intimacy and exhibition.

The performance of self-representation in public space is also reenacted through these stretched, gaping objects. They become desperate spaces due to their internal incompleteness, and unfold to the extreme. Nora Guislain also works with a selection of materials that evoke specific vocabularies and codes of seduction. These empty boxes are similar to individuals who force themselves to conform to norms, subject to the assumption that the only form of success is manifested in accomplishment.

The relationship to the object that emerges through this series of examples is neither one of anxiety nor nostalgia that would symptomatically follow its disappearance. Rather, it is one of renunciation.

There is no attempt to compensate for the absence or loss of what the box once held; it is interesting because it contained something, but no longer does. It has been stripped of the function for which it was designed and which it fulfilled, and yet it remains imbued with it.

This disuse does not make the jewellery box inferior or superior. It is neither alienation nor museumification; it neither gains nor loses, but simply changes status: the box becomes completely useless. Instead of trying to redefine things outside their original purpose, it is a matter of temporarily abandoning the quest for meaning in an overly verticalised universe. Appreciating this type of object could then be a specific reaction to uselessness, to things that escape the productivity cycle and are set aside without being thrown away (escaping their responsibilities?). They remain there, for nothing. Boxes that are completely open but without any expectation. Perhaps free? Or dead.